Welcome to “The Barnesville Buzz!” A buzz is a murmur, a quiet hum that can be amplified through great numbers of voices, hands, hearts, and minds, working in unison. A buzz is a state of movement, filled with energy, a busyness on the brink of chaos, yet perfectly orchestrated. This vibration is the spirit of joy that I carry into the classroom and that I encourage each of my students to embody through the process of art making.

Education as the Practice of Freedom

I’ve been reading so many wonderful books lately, including many by the legendary bell hooks (yes, she does not capitalize her first or last name). She’s a pioneer in the field of feminism, race, love, an education. In fact, with over 20 books in publication there’s few topics she hasn’t covered.

I first learned of her work last fall when I shared on Facebook an experience with becoming vulnerable in the classroom. An acquaintance commented on my post and urged me to read hooks’ Teaching to Transgress. In this book, and the two to come after it, hooks’ refers to “teaching as the practice of freedom.” Using her own experiences as a student and a teacher, she makes the argument for a model of education that seeks to liberate and empower students through learning.

Putting aside what some might call the “practical” applications of education, hooks’ firmly grounds her teaching practice in the belief that education is about nurturing a lifetime love of learning. Or, learning for the joy of learning. When education is seen through this lens, progressive teachers can create environments of learning that encourage students to be active versus passive participants.

Passive students become victims of our culture of domination, which relies on students being controlled and made into puppets of mass consumerism; And conventional models of education play an important role in making sure it stays that way. For over a century classrooms have looked almost exactly the same, while advances in technology have lead to innovations in everything from automobiles to entertainment. While each day offers a new set of products for consumers to buy, classrooms remain factories where teachers spew information and students are expected to sit quietly, memorize, and regurgitate:

“In our nation (schools) are organized around the principles of dominant culture. This organizational model reinforces hierarchies of power and control. It encourages students to be fear-based, that is to fear teachers and seek to please them. Concurrently, students are encouraged to doubt themselves, their capacity to know, to think, and to act. Learned helplessness is important for the maintenance of dominator culture.” (bell hooks, Teaching Community, pg.130)

When progressive teachers present students with opportunities to challenge dominant culture, education can become the practice of freedom. Freedom to see and be seen. Freedom to develop a set of values rather than inherit one. Freedom to become agents of change. Freedom to learn for the love of learning.

I recently asked my middle school students to respond to the prompt “Do you think grades are important?” As many of you might guess, almost all of the students said yes. It usually sounded something like this: “Yes, I think grades are important because if you don’t get good grades your parents will be mad, and you can’t get into a good high school or college, and you can’t get a good job, and you won’t have any money.” Not a single student talked about the lifetime benefits of being an engaged learner or attempted to critique the system of assessment. The end point was always money.

These students live in a culture where people have been lead to believe that having money to acquire things is what will make them happy. The eight hours a day they spend in school from the age of 3 to 18 is a mere stopping point on their way to a future where they might never read another book and they will transition from spending eight hours at school to eight hours at work in order to afford a lifestyle that promises happiness, yet rarely delivers it.

As a progressive teacher I am frequently disheartened by the emphasis on grades in this dominator culture. I’m asked to assign ambiguous letters and numbers to students based on a structure that prioritizes competition and uniformity. Students are never the same, and yet each time I grade I am asked to compare them.

An alternative argument for grades might be that they provide students with feedback so that they can improve their performance. I always have my students complete a self-scoring rubric and I’ve found that students generally know how they are performing. I use the self-scoring rubrics during one-on-one meetings where I will talk with students about something they have already realized they need to work on. Self-scoring rubrics help my students to reflect on their work and they include students in the assessment process more than traditional report cards.

Grades are also a poor incentive tool in that they are often used to force cooperation through fear. Teachers might threaten to lower a students grade any time they bring a critical perspective into the classroom. This encourages students to be compliant and to feel powerless, which can lead to an overall apathetic attitude towards education. And there’s a snowball effect in that teachers will then complain that students are unmotivated and disengaged.

Reading hooks’ writing has reaffirmed my desire to engage students in my classroom through the model of education the practice of freedom. Choice is a big part of how I seek to empower students by making it known that I value their input and diverse perspectives. I’ve also tried to minimize my reliance on conventional tools for controlling the classroom. If I ask a student to do something I always try to give them a reason and I don’t seek compliance for the sole purpose of maintaining my power.

Having been brought up in an educational system based on fear, this is a hard transition to make. I constantly have to check myself and learn from my mistakes. I’m mindful of how I use my authority as a teacher in order to set boundaries and when I can let go so that my students can learn to self-regulate. It’s a constant balancing act. Yet, practicing education as the practice of freedom has helped me to stay positive about my work even when the balancing act can be exhausting and overwhelming.

Executive Functioning in the TAB Classroom

(How do you deal with) students that struggle with executive functioning and other learning differences?

Teaching for Artistic Behavior is a great model for students that not only struggle with executive functioning, but a plethora of other academic, social, and emotional difficulties. TAB enables teachers to accommodate a variety of student needs and personalities because it is focused on creating a space where diversity is seen as an asset versus an obstacle.

I no longer teach media-themed or step-by-step lessons, which means I can maximize my time getting to know students one-on-one. I can collaborate with these same students on ways that they can overcome whatever their challenges may be using the model of choice. Vice versa, the rigidity of a step-by-step lesson usually gets in the way of students building confidence and self-advocacy because it is assumed that there is one solution, and that solution is dictated by the teacher.

Since the question at hand specifically has to do with students that struggle with executive functioning, I would like to share here how TAB has helped some of my students that are diagnosed with ADD, ADHD, and anxiety; Diagnoses that often present themselves in a student’s inability to focus, stay-on-task, or remember a set of directions.

A specific example of how I have been able to collaborate with students that struggle with executive functioning is by simply noticing when they are distracted and having an honest conversation with them about what they could do to keep them self and their artwork on track. Usually, students are able to come up with effective solutions on their own, the most common being moving away from peers and to parts of the classroom that are quieter. This sounds simple but the key is having the student generate the solution rather than the teacher telling the student what to do. When students know that their ideas are valued and that they are in charge of their own learning they will make choices that lead to their success. And they will repeat those choices again and again. In the past when I told distracted students to stop talking to their peers and move to another part of the classroom, I would have to remind them to do these things every class. Now, when I engage students in making this choice for them self, they no longer need me to remind them what to do.

Another way that I help students that struggle with executive functioning relates to one of the goals of a TAB classroom: minimize the amount of teacher instruction time to just 5 minutes at the beginning of class, and in this way, maximize the time students are making art. I do this by asking myself “What is the least amount of information I need to give for my students to get started working?” In this way my tendency to overshare is kept in check, but more to the point, information is broken down into smaller pieces and made concise. This is important for students that struggle with executive functioning because an excess of information can cause confusion and open the door to behaviors associated with distraction.

I am able to keep my instruction time short because I no longer give traditional step-by-step demos and because I have prioritized student learning through trial and error, or to use the TAB lingo, stretching and exploring.

So a typical class looks like this:

-Students line up outside and enter the room when invited in.

-Middle school students collect their sketchbooks and “Do Now” booklets. There is a prompt projected for them to respond to in their booklets, and the responses are graded at the end of each trimester. This allows time for everyone to arrive and get settled in before my 5 minute instruction begins.

-Lower School students join me on the carpet and I will read a picture book, we will brainstorm ways to achieve the habits of mind, or we will pair-share artworks that are in progress.

-All students go into centers until 5 minutes are left in class.

-MS students that are beginning a WOW artwork are given a planning form including a section called “Set Goals.” In this section the number of classes we have to complete the WOW are listed and students must write how they plan to use each class.

-For LS students I keep a Google Doc of what center each student visits each week and this helps me to make sure that students are getting equal access to all the centers, and likewise, that students are exploring outside of their comfort zones.

-At 5 minutes from the end of class, all students clean up.

-Any time a student completes a WOW work of art they are required to write a reflection, which I frequently call “the story of my artwork”.

I include this schedule to show that within my TAB classroom there is a tremendous amount of structure. This is important because we know that all students benefit from structure and especially those struggling with executive functioning. I also include this schedule because I think that sometimes when I first talk to parents or colleagues about TAB there is this perception that students are “just doing whatever they want”. I can understand this as an initial response to a teaching philosophy that may look very different than a parent/colleague’s own art education experience. However, it’s worth clarifying that (1) letting students do what they want comes with a lot of great learning outcomes and (2) students are doing what they want within a structure that prioritizes student success and does not indicate a lack of care or intention on the part of the teacher.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a classroom anywhere in which no student struggles with social, emotional, and/or academic issues. Diversity has been an inherent and essential part of human evolution, and that fact cannot be ignored when considering how best to teach students. For me, the TAB philosophy has provided an effective way to reach all types of students and build communities of art making that celebrate difference.

“Projects” and the Question of Quality

How will this (TAB) change the projects you make in art? Will the traditional projects change?

Something I am working really hard to do this year is to stop using the word “project” and instead use the word artwork. While there is nothing inherently wrong with the word project, if I want my students to see themselves as artists then they must also see what they are creating as art. But more to the point of the question, there will be no more projects in art this year, at least not of the teacher-assigned variety.

The framework of the art curriculum is the studio centers and the “projects” are the artworks designed and created by students in these centers.

I’m attached to my “traditional projects” just as much as the next adult, but the fact is my students are not. There are certainly some students who enjoyed my old projects but there were just as many who upon finishing asked if they could throw them away, or more subtly abandoned them in other classrooms and on top of lockers. While the results of these teacher-directed projects are great and I have had loads of fun coming up with creative lessons, fulfilling my own creative vision has frequently robbed my students of having ownership and pride in what they produce.

In the past, I almost always had at least one student ask in every class if they could do something that really broke with the mold of the project. This was always a difficult moment for me and I would frequently revert to the phrase “well that’s not really the point of this project.” I cringe writing that now because since switching to TAB I’ve really come to value those students who have the courage to question the status quo and take risks with their art making.

There’s another set of students for whom the switch has been slightly more complicated, and who (ironically) used to be among my favorite students. We might call these the rule followers. These students never questioned my projects or challenged my feedback. They made stereotypically “beautiful” work, taking their time and checking in with me frequently about their progress. I see now that these students were making work to satisfy me and my particular aesthetic more than their own. They were grade-motivated versus intrinsically-motivated.

This realization connects well with another question I have received frequently, which is:

Are students producing quality work with this open concept?

The short answer of course is that “quality” is subjective. I am currently in the process of grading the WOW artworks from trimester one and I was explaining to my husband that when I look at all the work together it is not always the ones that I like the best that receive the highest grade. I’m no longer just grading for the finished product, but instead I am looking at the whole creative process from envisioning, to planning, to research, all the way to the thing that hangs on the wall. I am also thinking about each individual student and what I know about their current skill level compared to what they produced for their WOW project as opposed to what everyone else produced. I suppose you could think of it as the students competing with themselves versus their classmates.

Something else that seems especially relevant to mention with regards to “quality” is that this is “student” work, the emphasis on student being that these kids are learning how to do something for the first time. There’s a lot of skills that need to be mastered before someone can produce quality work and many of those skills can only be learned through trial and error. Realizing this has helped me to see my students’ work differently, and especially those pieces that feel rushed, messy, or incomplete. That kind of work is actually really important because it provides feedback to the student about areas where they need to improve. Hovering over a student while they produce and telling them they are rushing is not nearly as effective as letting them learn that lesson on their own and having a conversation about how their tendency to rush is communicated through their artwork. They may not feel that they are rushing as they work, but they can see it in the work they produce.

When I first switched to TAB I was really worried about the fact that I had set this expectation about what the quality of the artwork at my school would be. I was nervous about hanging up student work that did not meet that precedent. Something that I find really encouraging about what the hallways of my school look like now is that they are filled with diverse styles and art media. They are an authentic representation of our student population, not what I think prospective parents or the administration wants to see. I also made sure to post pictures of each student and a written reflection next to the work, which gives context to each piece. It’s become more about visualizing learning and celebrating the individual than about fabricating quality.

How will younger students get all the skills they need to be independent at centers?

A couple of years ago I heard a podcast about an experiment where a computer was “dropped” in a remote village in India with no instructions. The researchers wanted to know if people, children specifically, of the village could teach themselves how to use the computer. I can no longer find that exact podcast but in looking for it I came across an article out of MIT about a similar experiment supported by the One Laptop Per Child organization. Here is a link to the article, but essentially what researchers have found is that yes, children can teach themselves how to read and write and were even able to successfully hack the tablets they were given, allowing them to customize their desktops:

Earlier this year, OLPC workers dropped off closed boxes containing the tablets, taped shut, with no instruction. “I thought the kids would play with the boxes. Within four minutes, one kid not only opened the box, found the on-off switch … powered it up. Within five days, they were using 47 apps per child, per day. Within two weeks, they were singing ABC songs in the village, and within five months, they had hacked Android,” Negroponte said. “Some idiot in our organization or in the Media Lab had disabled the camera, and they figured out the camera, and had hacked Android.”

Elaborating later on Negroponte’s hacking comment, Ed McNierney, OLPC’s chief technology officer, said that the kids had gotten around OLPC’s effort to freeze desktop settings. “The kids had completely customized the desktop—so every kids’ tablet looked different. We had installed software to prevent them from doing that,” McNierney said. “And the fact they worked around it was clearly the kind of creativity, the kind of inquiry, the kind of discovery that we think is essential to learning.”

I’ve thought a lot about the implications of this study from the perspective of both children without access to education and also as someone who is in the profession of teaching. Mostly, I’ve thought about how in the past I made assumptions about what my students knew or did not and the skills I needed to teach them. There are developmental stages, benchmarks, and “rights of passage” that almost all children go through and being familiar with the psychology of child development is an important part of my job. There are also lots of ways that children already possess the power to acquire skills on their own, with minimal intervention on the part of the teacher.

Just the other day I had a group of 1st graders painting with watercolor. I listened to them discuss the various shades of blue they were creating and discover the way that different ratios of paint to water affected the transparency of the colors they were mixing. One student problem-solved a potential disaster when she suggested to the group that they move the paint and water cup further away from their papers to prevent spills. At one point I noticed the same student struggling to reach across her paper to paint the far side and in one of the only moments I intervened I suggested she might rotate her paper to make it easier. Later on she was dancing in her seat while painting and announcing to the class “Guys, I’m gonna spin this.” And she did spin her paper, sharing with her peers how they too might benefit from this tip.

I don’t think that my job as a teacher is made irrelevant by OLPC’s research, but I do think that this research shows how capable children are. There is a tendency to focus on teaching “skills” when what we might consider focusing on is creativity and curiosity. When we model to students how to ask questions and when we give students lots of opportunities to problem-solve creatively, we provide the foundation for them to learn skills independently. Nowadays, instead of rushing to “teach,” I eagerly await moments of eavesdropping, when students tell and show me all that they already know. My teaching practice has become about listening, offering feedback, and maximizing time for students to work, create, and discover.

How do you inspire kids that are stuck?

I recently gave a presentation to my colleagues about my switch to TAB. Rather than taking questions during or at the conclusion of my talk, I asked my peers to write down their questions and reflections on papers, which I collected at the end. My intention was to respond to each question in a single email, but when I sat down to write I realized that I have a lot to say. It also occurred to me that the kinds of questions I was getting were similar to those I had asked myself before switching to TAB, and that maybe there’s a larger community that would benefit from hearing my perspective. So I am launching a blog series in which I will respond to these questions one-by-one, or in some cases group similar questions and responses together. Up first…

How do you inspire kids that are stuck?

Being “stuck” is a familiar feeling. It’s uncomfortable, and worse, unproductive. Children and adults have learned to be afraid of being stuck because we live in a culture that values comfort and efficiency. If you’re not always producing, on the go, or sleep-deprived, you aren’t doing it right. The word “stuck” itself is a value judgement on time that might otherwise be described as contemplative.

Being stuck is an indication that students haven’t had many opportunities to design their own learning, to be creative, and independent. This happens in schools where the teacher makes all of the decisions. In cases like this the only way for students to become independent, productive, and unstuck is to experience the whole artistic process, even the parts at the beginning that are a little uncomfortable.

When I have a child that is stuck I try to avoid rushing to their rescue. I want them to sit with the feeling long enough that they give them self an opportunity to come up with an idea, and to own that idea because it came from within. I want them to wander around the room, looking at and touching things that they find interesting, or to spend an entire class collecting images they like in a Google Doc. I want them to be what some might call “in-efficient.”

One way to think of an artwork is as an answer to a question or a solution to a problem. If students can come up with a question that’s usually enough to get them going. I model different kinds of questions one could ask by first asking students what they are interested in. Once we land on something (and there is always something), I let them feel like the expert: Tell me everything you know about this topic. Now tell me some questions you still have, some things you’ve been wondering about, some “what ifs..” This model inspires student confidence and helps them to generate ideas all without the teacher ever giving the student an idea.

Another way to think of being stuck is not that students don’t have any ideas but that they do not believe their ideas are good ones. Lots of times when a student finally works up the courage to reveal their idea it relates to areas of their life that they categorize as play; And because most children don’t think of school as a place where they can play they also don’t think that finding connections between their play and their work is acceptable.

An example would be a student that waits all day to get home and play video games. In the art room they might want to explore the places and characters they spend time with in these digital worlds, but they are afraid to share their ideas about artwork inspired by video games because the teacher could say that the subject matter is not academic. This is a legitimate fear because sadly some teachers do have that response. In my room, however, I try to prioritize the word “yes.” Except in cases of something extremely inappropriate, offensive, or at odds with the school’s mission, if students have an idea and are excited about it, then that’s the idea I want them to pursue.

The Truth About Paper Airplanes

In the fall of 2017, I went to my head of school with an idea. It was a drawing of what my art room might look like if it were to be combined with an adjacent classroom. Over the next months, I continued to meet with administrators and to develop the idea further. By the spring, the proposed renovation had become a major part of the “special appeal” at my school’s yearly gala, and some of my very own colleagues were among the many generous donors to raise their paddles. The funds raised through this event made it possible for my dream to be realized when the wall between my original art room and the other classroom was taken down over the summer of 2018.

I think most teachers would agree that having a bigger space is beneficial to students for all kinds of reasons. Larger spaces accommodate group work, provide quiet corners for students that need to work independently, and room for students to spread out while working on posters and other large projects. In an art class, space offers the ability for students to pursue large-scale and sculptural works of art with storage being more plentiful.

Along with the physical renovation my classroom received this summer, my teaching philosophy underwent a similar over-haul. Beginning last spring, I started re-developing and refining my approach to art education through copious amounts of research and reading. I was inspired by the many workshops I have attended on choice-based art at the annual Art Educator’s Conference over the past two years. Choice, also known as Teaching for Artistic Behavior (TAB) is growing in popularity among art teachers, and at the heart of why I sought to expand my classroom to begin with.

The TAB curriculum is comprised of just three sentences, but what it offers students is far more than traditional media or theme-based approaches to art. The curriculum is:

What do artists do? The child is the artist. The art room is the child’s studio.

In the TAB classroom, students are assumed to be artists and treated as such. These artists take ownership over their class room, which in turn functions as an authentic art studio. In this art studio, students practice the habits that all artists use: Envision, Observe, Stretch and Explore, Engage and Persist, Reflect, Develop Craft, Understand Art Worlds, and Express.

Artists produce all kinds of studio work from “Wonderful Works of Art” (WOW) to sketches and explorations. All of the research, planning, collecting, and reflecting that go into getting to a WOW piece of artwork is considered equally during assessment.

Some of the goals of TAB are to:

-foster independence through choice

-accommodate diverse populations and skill levels through an expansive versus restrictive curriculum

-nurture creativity by validating each child’s unique set of interests

In the TAB classroom, media are separated into distinct centers and students are given great choice in which centers they visit and what kinds of artworks they pursue. Examples of centers that I will offer this year include: drawing, painting, paper art, mixed-media sculpture, ceramics, digital art, printmaking, fiber arts, and photography. These centers will open in the order they appear above, with a new center available on average every two weeks. By the end of the year, all centers are open.

The art studio expansion was a key component in my being able to realize the TAB philosophy in that centers generally require a great deal of space, as does storing diverse work from 100+ students.

I’ve been teaching in my new space for around a month now. Although I have been moving towards a choice-based art room since last spring, the switch to TAB is dramatically different than the routines that most students associate with art, not to mention nearly all of their other classes. So I have been sure to make the transition slowly and to scaffold students with lots of structure, class discussion, and visual aids. We’ve spoken at length about the TAB philosophy, how to generate ideas, and my expectations for how class time will be used. The drawing center officially opened this week, and 2nd-8th graders are busy envisioning, exploring, and reflecting.

I too am reflecting as I watch some students run with excitement to the drawing center, while others look up at me perplexed, then ask “Wait, do you really mean I get to come up with my own artwork?” The answer of course is, yes.

On Tuesday and Wednesday I had lower school classes. The drawing center opened and almost all of the students in 3rd and 4th grade started making paper airplanes. Once they were flying about the room, I started to second guess everything I was doing and immediately cringed at the thought of an administrator or colleague walking past the room. Would they think I was lazy? Or irresponsible? That there was no way this was intentional because what are you teaching kids anyway if you let them spend the whole class making paper airplanes?

As it turns out…you are teaching them a lot.

Once I had quieted my inner critic and began listening to the conversations students were having about their planes, my confidence in TAB was restored. For whatever reason, paper airplanes have gained this horrible reputation as non-serious, juvenile, and disruptive. But when I listened to the conversations my students were having about their planes and watched how they were working collectively, a different narrative emerged:

Students were speculating about how the size and wing span of the plane could effect how far it would travel. They were decorating their planes using different drawing materials in order to make the planes more unique and to represent their interests. One student asked me to spell out the names of half a dozen characters from the musical Hamilton because she was making a Hamilton-themed plane. A couple students did not have as much experience making planes and so my best plane folder, who also happens to be one of my less-confident artists, started teaching those other students how to fold them.

To avoid having planes flying all about, I told students we would have an air show at the very end of class, and this inspired even more students to take on the task of carefully folding and decorating their own planes. Before the air show we lined up all the planes on a table and I had students describe what qualities their plane had that they predicted would help it to fly the farthest. Then we tested our hypotheses as one student after another launched their plane down the hall.

Some students mentioned that it would have been great to test their planes ahead of time so they could make improvements. I agree and next class I will designate a spot in my room for them to do so. I’m also planing to check some books out of the library on folding airplanes, plus making available some general origami references.

The term “Emergent Curriculum” appears a lot in TAB philosophy and describes when a teacher designs curriculum based around the specific skills, needs, and interests of a group of students. This approach facilitates a high degree of student engagement because the students can actually see themselves reflected in the classroom. Math, science, reading, writing and other subjects can be easily integrated into the curriculum all within the context of what students are already interested in. An example of this would be the paper airplanes: within a one hour class period students practiced fine motor skills, collaboration, geometry, and physics. Now that I am aware of the students’ interest in paper airplanes, I can seek out ways to make more cross-curricular connections with greater intention.

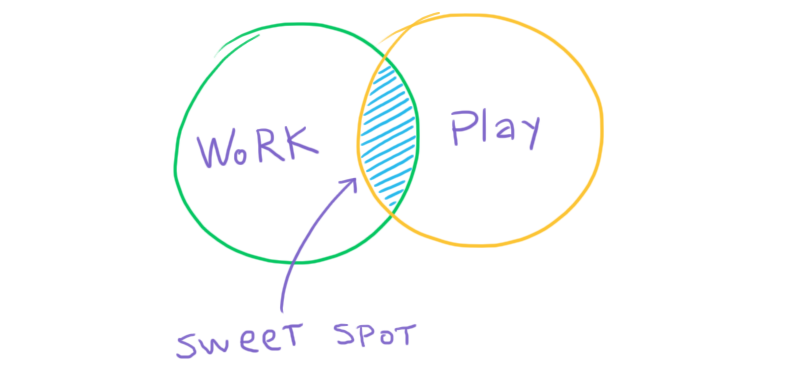

When students feel that their interests are validated by the teacher, a relationship of trust is formed and the student is more receptive to other kinds of materials and experiences the teacher may want to share. Skill-building is no longer forced, and work becomes play.

I am excited to continue sharing my experience with TAB and expect that many of my parents will observe changes in their child’s relationship with art class over the course of the year. I hope that in sharing how I am building my TAB classroom from the ground up I can help parents and other teachers understand the value in choice, and I myself can continue to reflect and improve upon my teaching practices.

Meet Mark

Last spring, I introduced seventh graders to the sculptures of Mark Jenkins, a local artist from Washington D.C. Jenkins who uses tape and plastic wrap to create plastic casts of people and objects. He then places his sculptures in various environments, some clothed and others partially translucent, with the process of casting left visible.

The sculptures run the gamut from serious to mischievous, humorous, and disturbing. They often draw the attention of police when a passerby, tricked into believing a sculpture is real, reports it to 911. Many of these clothed sculptures appear to be homeless, or at the very least speak to the feeling of emotional isolation. Closer inspection would surely reveal that they are not real, which makes me reflect on the distance we so often put between ourselves and those considered different, perhaps even dangerous. We choose not to interact, to avert our eyes, while casually dropping coins into re-purposed containers. Or worse, we wait for the next person to come to the rescue, which inevitably leads to a kind of bystander apathy. In both of these scenarios our own comfort wins out while we move through the world paralyzed by the thought of confronting our personal biases, assumptions, and widely-held stereotypes.

Jenkins’ clothed figures have an especially powerful effect in the way that they startle and surprise. His work reminds me of that strange mix of fear and exhilaration I get when riding on a roller coaster. In the image above we see three men, completely concealed by hoodies, ski masks, gloves and other articles of clothing. They sit, each with a baseball bat in their hands.

When I talk to students about work like this (or any image for that matter) I am always curious to know what they notice first. Their responses, and the order in which they come, provide a glimpse into our brains’ thought processes and our collective biases. These conversations are more important than anything else that happens inside my classroom because they prompt students to observe not only images, but the way we absorb information and interpret it.

A (fatal) love affair with efficiency:

Each day we are inundated with thousands of images, and even more so in our technology-driven world. In order for us to process all of this visual information our brains need to be able to “read” images efficiently. This process helps us to categorize, store, and retrieve information quickly, so we can do things like recognize people we know next to people we don’t; a shirt next to a sock- can you imagine how long it would take to sort through a basket of laundry if we could not distinguish between the two?

The examples above are just two of the many practical reasons why our brains have developed to work this way, but a consequence of this efficiency is that it opens the door to all kinds of stereotyping. One way that I help students to recognize the “pitfalls of efficiency” is to teach them to closely observe images and artworks and to notice the assumptions they make surrounding issues such as race, gender, and sexual-orientation, just to name a few.

If I can return for a moment to the image above: I observe that the figures are probably men, wearing hoodies, ski masks, gloves, and holding baseball bats. They are also wearing long pants, high socks, and shoes. Nowhere is any part of their skin or hair showing. They are sitting down in a public space, all three gazing at the tile floor in front of them. If I were in the space with the sculptures, and if I stopped to look at them even for 30 seconds, I would probably realize quickly that they are not real. But if I was walking by, my brain would see the ski masks, the bats, the gloves…now I am turning around and walking the other way or picking up my pace to move quickly past them.

I’ve observed three things about the entire scene and decided it’s unsafe to get any closer. While I’m walking away, my heart rate begins to slow down and I start to build a narrative around what I have just seen, only I haven’t really seen much at all. Maybe in my narrative the men are black and they are waiting to attack. They’re probably gang members out to get retribution. They are moral-less and uneducated. Before I know it, I have constructed an entire story around three articles of clothing.

In this case, I have the benefit of being able to look back at the photo again, see that the men are completely covered, and that there is no possible way for me to know their race. I can take apart my thought process and begin to see how the ideas I have inherited about black men and violence are so powerful that they exist even outside the observable facts of a situation.

Some of you might be thinking, well okay but we need to be able to make judgments quickly in order to protect ourselves from danger. To which I would say, this is true but not to the extent of our ancestral cavemen and women. I think the main problem here is that our bodies haven’t quite evolved to function within the world we now live. And perhaps more problematic, we continue to teach fear at the expense of seeking to understand and connect with people different than ourselves.

The Project:

All of this looking, and thinking, and reflecting is an important part of how I try to start every project with my students; And so with my seventh graders we started by looking at a wide range of Jenkins’ artwork and talking about how he uses the environment to contextualize his sculptures and to break with the model of the white cube gallery. He uses humble and relatively inexpensive materials, not normally associated with fine art. He takes his work and its ideas into unconventional spaces, making the artwork accessible to a wide range of people, not only museum-goers.

Using Jenkins’ tape casting technique, seventh graders worked in groups to create sculptures of people (themselves), which they then installed at locations around the school. They could choose to clothe their artworks or keep them as they were, but all of the sculptures needed to interact directly with the environment in which they were placed. Casting proved difficult, especially as supplies became depleted (for future reference, it takes a whole lot of tape), but in the end we had at least a couple of sculptures that retained their form, and when dressed, were startlingly realistic.

The students loved this project. You could hear their enthusiasm in the giggles that filled the art room as they wrapped one another, and you could see it in the care they took displaying their projects around our school.

Then came some concerns about the artworks’ potential to frighten younger students and a few subtle requests to relocate certain pieces. As an artist these are the kinds of moments that I both look forward to and dread. I look forward to them because they are an opportunity to educate our community about the ideas and artists that have motivated the artwork; And in this case, to explain why exhibiting artwork in unconventional spaces is an important tool that artists use to question how artwork is presented and for whom it is accessible. It is a moment I dread because my initial reaction is often to feel under attack and I retreat from the opportunity to express my ideas and values in order to avoid conflict. I can say this comfortably because I know I am hardly alone in this feeling and because it is something I continue to work on within and outside of my school community.

In fact, I had all but forgotten about the requests to relocate the artworks when something (the very impetus behind this post) transpired.

When Fear is the Elephant in the Room:

Sometime during the weekend of a major wind storm, the power went out at school, causing the alarm to go off, and the police to show up. A staff member was at school during this time and later told me that when one of the officers approached the front of the building and spotted one of my seventh graders’ sculptures (below), he placed his hand on his gun. In case the photo is not clear, this is a child-sized sculpture sitting in a chair, clothed in sweatpants, a hoodie, bearing no weapons, and not displaying them self in any kind of threatening manner. Needless to say, I was shocked and mortified.

I was not there and cannot attest to the accuracy of the story or its re-telling. Nevertheless, I am deeply concerned by what it communicates about the current relationship between the police, students, schools, and gun violence. Without intention, the group of students that worked on this sculpture created a situation that perfectly reflects the fears and anxieties that are surging through schools and communities around the country, including our very own.

I thought about this story more and more in the days and weeks that followed: Okay, it’s the weekend, the alarm has gone off, perhaps there’s been a break in, maybe the intruder is still inside…maybe all of those things are true, and there’s a “child” hunched over in a chair with a hoodie on. The officer’s heart rate most likely increased, a momentary rush of fear running through his veins.

That feeling is what Jenkins is after when he creates and displays his work because it is what brings his figures to life. Surprise, even fear, at an artwork’s realness pulls his audience in and hooks them emotionally. And as we all know, emotion is at the heart of almost every choice we make. It is as powerful as reason, and sometimes more so. It connects us to objects, and places, and people…even plastic ones. So when we talk about emotionally-charged artwork, it is about creating the connection between object and audience that allows moments of vulnerability and reflection.

Mark Jenkins’ “84 Men” Installation For Suicide Prevention

So whether we call it surprise or fear, this feeling I am talking about connects seamlessly with what happened with the officer and the gun by underscoring the major role that emotion can play in matters of life and death. The responding officer (hypothetical or otherwise) was scared and in that moment failed to observe all parts of the picture, to contextualize the situation and the likelihood that an alarm went off because of an intruder versus the windstorm that had already downed a number of trees.

As long as we have a human police force we will never have a completely objective one. But there are ways to minimize emotionally-reactive decision making, and dare I say, chip away at this deadly culture of fear. Learning to notice how you respond emotionally in different situations and with different people is one way. While looking closely at how we interpret images, perpetuate stereotypes, and breed all kinds of “isms” is what I seek to do as an important part of being an art educator.

What strikes me most in all of this is the potential to change the way our youngest people learn to read the world around them, and consequently, to save lives. Students that learn to look at things closely and critically not only dispel the lies of stereotypes but they also learn to recognize real threats. Students that are indoctrinated into a culture of individualism, hate, and fear of the “other,” never learn to be critical thinkers nor to reap the benefits of self-awareness and interpersonal connection.

The views expressed in the post are wholly my own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of my colleagues or other members of my school community.

Some of the information presented in this post is hearsay and cannot be substantiated. It is included for its remarkable similarity to incidents of police misconduct that have been documented.

How to…ZINE!

Zines are low-tech self-published magazines made by artists and distributed in small batches. They can be made up entirely of images or combine image and text, and they address a wide range of topics from the humorous to the political.

Sixth graders wrote and designed their own zines based on the prompt “how to…” They learned to create handmade paper, which they used for the covers of their zines. Then they used Google Docs to experiment with different fonts and page layouts. They printed their text leaving room to paste in drawings and photographs. The collaged draft was then photocopied, unifying text and image and giving the final artwork that quintessential look of a zine.

Once more with Rousseau

I returned to this lesson again after several former third graders told me it had been their favorite.

Using an array of materials, students constructed a diorama based on Henri Rousseau’s jungle paintings. We learned to draw various animals using instructional books and images printed off of the web. The animals were cut out and inserted into the dioramas, where students also used feathers, fabric, stones, moss and other materials to build out the environment.

This project offers students lots of opportunities to problem-solve and be creative with everyday materials. By combining sculpture with illustration, students can move between different modes of making and this seems to create the right balance for keeping students engaged.